what would it take to bring both coutries together to solve the trade war

World Trade and Problems of Developing Countries

Let us make an in-depth study of the trends in world merchandise and issues of developing countries.

Bailiwick-Thing:

International trade and international investment take grown speedily since the starting time of Industrial Revolution (1740).

For example, exports as a percentage of full national output grew from just i% of the total value of world output in 1820 to nigh 14.1% in 2002. The process that we often refer to every bit globalisation in fact appears to be related to the economic growth that nations accept enjoyed over the same flow.

The increasingly close human relationship between economies, or globalisation, involves more simply the growth of international trade in appurtenances and services. The flows of capital and people across national borders have also been growing rapidly in recent years.

Several recent economic crisis in developing countries such as the Mexican crisis of 1994 and the Thai currency crunch of 1997 have been linked to international majuscule mobility. This very fact suggests that capital flows can, under sure circumstances, wearisome economic growth. In fact, international lending, investing and help are to all linked to economic growth in more than ways than ane.

There has occurred a rapid growth of globe trade in the past two centuries (since the time of Britain'due south industrial revolution). Notwithstanding, merchandise patterns today are quite different from those of the 19th century. Product at the centre of the world economic system tends to be resource-saving instead of resource-using, and synthetics take replaced many raw materials. Furthermore, the trade policies of today's industrialised countries are less liberal than those of the 19th century, which had no multi-fibre agreement (MFA) or common agricultural policy of the eu (CAP) of Eu and no counter- veiling duties on Brazilian steel.

After World War I, tariffs rose sharply in both the U.s.a. and in Europe. In addition, many countries started to apply quotas and other controls to protect their economies against the spread of the depression. Merchandise liberalisation began in 1947 with the signing of the General Understanding on Tariffs and Trade and first rounds of GATT negotiations.

During the 1950s, protectionist pressures in the U.s.a. slowed downwards trade liberalisation, just information technology regained momentum with the formation of the EEC, and the Kennedy Circular of tariff cuts. In the 1970s, merchandise liberalisation took a new track. In the Tokyo Circular, governments attempted to reduce non-tariff barriers, along with tariffs, and agreed on codes of behave dealing with regime purchases and with subsidies and dumping.

But protectionist pressures built up strongly in the 1970s and 1980s, when economic growth slowed down and unemployment rose especially in Europe. The new protectionism likewise testifies to the success of previous trade liberalisation. Economies have go more open up and more sensitive to global competition. Old industries such every bit textiles, steel and automobiles have been exposed to intense competition from new producers and new industries.

Growing protectionist pressures have also led to the more frequent use of antidumping and counter-veiling duties and to the introduction of marketplace-operating measures in place of more than traditional GATT procedures for settling trade disputes.

In curt two distinct trends have emerged in the post Second World War menses, viz.:

(1) the growing use of non-tariff barriers to protect domestic industries; and

(2) the frequency with which dumping past foreign firms and subsidies past foreign governments accept been used to justify protectionism.

In full general, developed nations consign mainly primary products, viz., food and raw materials in exchange for manufactured goods from developed countries. Until the 1980s, it was widely believed that international merchandise and the roleing of the present international economic organization hindered development through failing terms of trade in the long run and widely fluctuating consign earnings for developing countries.

This is why evolution economists advocated industrialisation through import substitution (i.due east., the domestic production of manufactured appurtenances previously imported). They did not place much reliance on international trade for promoting growth in developing countries.

They also advocated reforms of the present international economic organisation to make it more responsive to the special needs of developing countries. But most economists today believe that international trade, based on comparative advantage, tin contribute significantly to the process of development of LDCs.

Developing countries are mostly more than dependent on merchandise than are developed countries. While large countries are understandably less dependent on trade than are small countries, at any given size, developing countries tend to devote a larger share of their output equally merchandise exports than do adult countries.

Big countries similar Brazil and Bharat, which take had unusually closed economies, tend to be less dependent on foreign trade in terms of national income than relatively small countries similar those in tropical Africa and East asia. On the other paw, LDCs like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, etc. are more dependent on foreign merchandise in terms of its share in national income than the very highly developed countries are.

The greater share of developing country exports in Gross domestic product is probably due in function to the much college relative prices of non-traded services, in developed than in developing countries. Moreover, the exports of LDCs are much less diversified than those of the adult countries.

1. Deterioration of the Terms of Trade:

According to some economists such as Prebisch, Vocalizer and Myrdal, the commodity terms of trade (which is the ratio of the cost index of exports to the price index of imports) -tend to deteriorate over time.

There are two main reasons for this:

(i) Productivity increase:

Most or all of the productivity increases that accept identify in developed nations are passed on to their workers in the grade of loftier wages and income. But productivity increases in developing countries lead to fall in commodity prices.

(ii) Income elasticity of need:

The demand for the manufactured exports of developed nations tends to grow much faster than the latter'due south demand for the agricultural exports of developing countries. This is due to much higher income elasticity of demand for manufactured goods than for agronomical commodities. For these reasons, cocky-sufficiency (no merchandise) is at times amend than trade. As J. N. Bhagwati has argued, the deterioration in the terms of trade of developing nations could be then groovy as to brand them worse-off with trade than without it. This is known as immeserising growth.

2. Export Instability and Economic Development:

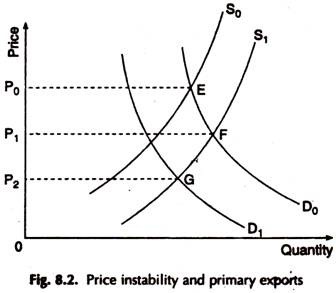

McBean has pointed out, apart from deteriorating long-run or secular terms of trade, developing countries may face up large short-term fluctuations in their export prices and foreign exchange receipts that could seriously hamper their development. This point is illustrated in Fig. 8.ii. D0 and S0 refer, respectively, to the demand and supply curves of developing countries.

With D0 and S0, the equilibrium price of primary exports of developing countries is P0. If D shifts to D1 or S to Si, the equilibrium price falls sharply to Pi. If both D and Due south shift to D1 and Southward1 the equilibrium price falls even more to P2. If D1 and Southward1 again shift back to their original positions, i.e., D0 and S0, the equilibrium price moves back upto P0.

Thus, toll inelastic and unstable D and Due south curves may lead to abrupt price fluctuations. Here the range of cost fluctuations is fairly wide P0-P2. Thus inelastic (i.e., steeply inclined) and unstable (i.eastward., shifting) demand and supply curves for the primary exports of developing countries can lead to large fluctuations in the prices of the exportable products of developing countries.

The demand for primary products in world markets is both cost inelastic and shifting. It is toll inelastic considering near households in developed countries spend only a small proportion of their income on such commodities every bit coffee, tea, sugar and cocoa. Consequently when the prices of these items alter, households practice not increment their purchases of these items much.

As a result the need for such items becomes price-inelastic. On the other paw, the demand for various minerals is cost inelastic considering substitutes are not readily bachelor. At the same time, the demand for the master products of developing countries is unstable because of trade cycles in advanced countries.

The supply of most primary exports developing countries is price inelastic considering of long gestations menstruation in case of tree crops, especially plantations. Condom trees require 10-15 years to grow. Moreover nosotros find internal rigidities and inflexibilities in resource use in most developing nations. Supplies are unstable and shifting considering of weather conditions, pests so on.

Due to broad fluctuates in export prices, the consign earnings of developing countries also vary significantly from year to year. This in its turn leads to fluctuations in national income, consumption, savings and investment. This type of economic fluctuations or business cycle motionments return development planning (which depends on imported machinery, funds, raw materials) much more than hard.

International Article Agreements:

Some developing countries, especially in Africa, have attempted to stabilise export prices for individual products by purely domestic schemes such as the marketing board set after Globe War II. These operated by purchasing the output of domestic producers at the stable prices set by the board, which would then export the commodities at fluctuating world prices. In years of bum-pest crops, domestic prices would be set below earth prices and then that the board could accumulate funds, which it would then disburse in bad years, by paying domestic producers higher than world prices.

Yet, international commodity agreements offered most developing countries a strong chance of increasing their export prices and earnings. Such agreements are of three types: buffer stocks, export controls, and purchase contracts.

Buffer stocks involve the- buy of the article (to exist added to the stock) when the commodity toll falls below the agreed minimum price, and sale of the commodity. Out of the stock its open market price rises above the established maximum toll.

Consign controls seek to regulate the quantity of a commodity exported by each nation in club to stabilise, commodity prices. This method completely avoids the price of maintaining stocks.

Purchase contracts are long-term multilateral agreements that fix a minimum toll at which importing nations agree to purchase a specified quantity of the commodity and a maximum toll at which exporting countries concord to sell certain fixed amounts of the commodity. Buy contracts thus avoid the disadvantages of buffer stocks and consign controls only result in a two- price system for the commodity.

Source: https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/trade/world-trade/world-trade-and-problems-of-developing-countries/12947

0 Response to "what would it take to bring both coutries together to solve the trade war"

Post a Comment